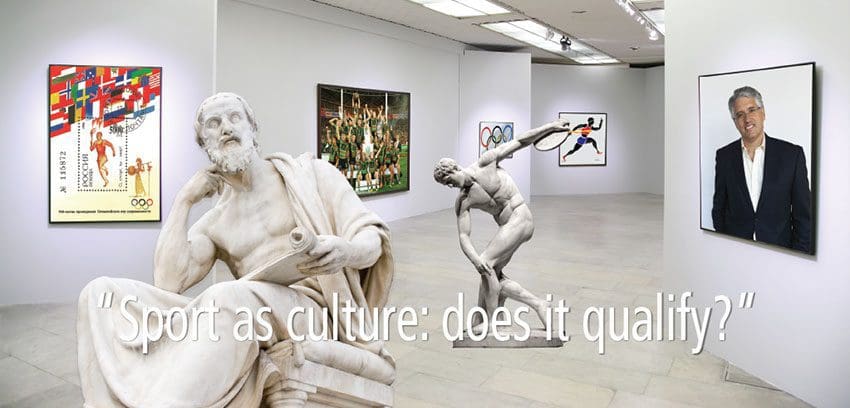

The Appreciating Culture Lecture 2015

Guest Speaker Dr Nicholas Pappas, AM

The Arts Exhibition 2015

Works by Students

Tuesday 26th May 2015

Sport as Culture: Does it Qualify?

Quite appropriately, I begin this talk tonight with this striking image of a grave stele found in Piraeus which dates from the first half of the 4th century BC. The original is to be found in the National Archaeological Museum in Athens.

The scene is from a ‘palestra’, the place where athletes trained and competed in ancient Greece. A young athlete, probably the deceased commemorated by the stele, practises a game which is not depicted or documented in any other ancient representation or literary source. He is clearly trying to balance or bounce a round ball on his right knee while standing on his left leg, his weight on his toes and his right arm behind his back gripping his left wrist. In front of him, a young slave attendant observes his skill while holding his master’s strígil and ar.ballos (oil container). On the column behind the athlete is his robe.

This is an image of grace and agility that resonates with us today precisely because it is so remarkably similar to something every young soccer player does in his or her warm-up. Fast forward two and a half thousand years and here you have an image of none other than the great Cristiano Ronaldo performing the very same routine. The only obvious difference is modern modesty which has thankfully led to the wearing of at least briefs while engaging in sport, something the Classical Greeks 2 frowned upon. But the underlying principle is clear: in two and a half thousand years very little has changed and humans continue to take delight in engaging in, and observing and admiring, such sporting dexterity.

But is this culture? This is the theme of my talk tonight which will hopefully take you on an interesting journey backwards and forwards through history to see if sport and culture do ever coalesce. Put another way, is sport a valid representation of society’s culture and its aesthetic and artistic achievements? Or is it merely an idle past time, or perhaps even just an outlet for legitimised, and sometimes illegitimate, violence.

I begin with an image that is at first innocuous but deeply sinister on closer inspection. This is a photo from Poland in 1940. It comes from a photo album of a German policeman in Nazi-occupied Lublin. The handwritten caption of the photo in the owner’s own photo album reads: ‘Sport in Poland: helping the Jews to learn how to play!’

The caption is striking for the triviality it attaches to the sheer brutality of what is actually going on. These Polish Jews are not engaging in voluntary sport or personal recreation. These are arrested Jews being publicly humiliated by being compelled to partake in a bizarre form of tug-of-war. If you look closely, there are two ‘teams’ of elderly men pulling with their teeth in opposite directions on a wire that is passing through their mouths. The humiliation is palpable, as is the delight of their captors. I show this awful image not to shock this audience. Rather, I think it demonstrates quite powerfully that sport, if it is to be elevated to the rank of culture, must be first and foremost a consensual act with its own set of rules based on fairness strictly applied. The Jews in this image, all of whom would be later executed, were anything but willing participants. While the owner of the album described the occasion as ‘sport’, and was clearly proud of the bizarre scene it displayed, no objective viewer with any sense of humanity would ever class this as true sport. Competition is one thing, wanton brutality and callousness another.

I show this awful image not to shock this audience. Rather, I think it demonstrates quite powerfully that sport, if it is to be elevated to the rank of culture, must be first and foremost a consensual act with its own set of rules based on fairness strictly applied. The Jews in this image, all of whom would be later executed, were anything but willing participants. While the owner of the album described the occasion as ‘sport’, and was clearly proud of the bizarre scene it displayed, no objective viewer with any sense of humanity would ever class this as true sport. Competition is one thing, wanton brutality and callousness another.

To lighten the tone, and with apologies to Bulldogs supporters in the house, it will not surprise any of you in the audience tonight that I am showing this triumphant image from 2014. This was undoubtedly a great evening in Australian sport, and one that will long be cherished, especially by South Sydney supporters. After a 43 year drought, a club that had been the pariah of Australian rugby league had reclaimed its place in the Australian sporting landscape as the number one sporting franchise in its code. Images from that night flooded the social and print media. People danced in the streets.

But what were they really celebrating? Were they just vicariously rejoicing in the athletic deeds of Greg Inglis and Sam Burgess? Or was there something deeper? More to the point, does the ‘tribal loyalty’ to a sporting team these supporters openly displayed qualify as an embodiment of culture for a modern, enlightened society? Of course, the 2014 Grand Final was not without its own measure of brutality. Many of you will recall that the first tackle of the match left Sam Burgess with a badly depressed cheek-bone which had him momentarily dazed and had us genuinely concerned for his wellbeing. Thankfully, he endured the match and even won the Clive Churchill Medal as the match’s best and fairest. He even earned an embrace from his assailant at the end of the game, but there can be little doubt that rugby league is the closest modern spectacle to gladiatorial combat.

Of course, the 2014 Grand Final was not without its own measure of brutality. Many of you will recall that the first tackle of the match left Sam Burgess with a badly depressed cheek-bone which had him momentarily dazed and had us genuinely concerned for his wellbeing. Thankfully, he endured the match and even won the Clive Churchill Medal as the match’s best and fairest. He even earned an embrace from his assailant at the end of the game, but there can be little doubt that rugby league is the closest modern spectacle to gladiatorial combat.

Frankly, I am amazed each week when I enter the dressing rooms and see the state these young men are in; not just from the injuries they suffer, but also from the sheer mental intensity required of them just to compete. They are all, at match end, utterly exhausted, almost to the point of bewilderment. Could this ever be culture?

The Romans, who prided themselves on their love of culture, loved the far harsher brutality of gladiatorial combat, but they reserved that privilege to prisoners of war and slaves. Losers would invariably be killed, but they sometimes survived if they had fought bravely and won the hearts of the spectators who would wave a white handkerchief as a sign of pardon. Even women fought in the arenas from time to time. Today, we would never call such brutality ‘culture’, but the Romans thought it truly was.

Gladiatorial contests were an important part of a calendar of public events in Rome and in regional towns across the Roman countryside for over 500 years, until banned by the Christian emperors. For example, we know from Pompeii that the rivalry between the gladiators of that town and the nearby town of Nuceria was so intense that it led to a massive riot in 59 AD in which hundreds lost their lives. There was such public outrage at the violence that gladiatorial contests were banned in both towns to stop further bloodshed and damage. By the time Vesuvius erupted twenty years later there were still substantial unrepaired traces of the riot, such was the scale of the damage.

So, what is sport anyway? While there is still some dispute, most etymologists agree that the word has its origins in the old French term desporter which means ‘to take away’ or ‘to distract from one’s work’; basically a pastime or anything that offers pleasure away from the mundane routine of daily life. Of course, the ancient Greek, and indeed modern Greek, word for sport was athlitismos. An athlitis was a person who competed for a prize, someone who toiled for a cause, from the ancient Greek verb athleo. The prize was the honour of victory, rather than any bounty.

This was carried into Latin – athleta – and ultimately into English in the words ‘athlete’ and ‘athletics’. But the etymological root of athlitismos has a very different connotation to our modern word ‘sport’. For the ancient Greeks, to engage in athlitismos was to compete, to struggle and to win with honour. It was closely connected to art, to music and to the study of medicine. Contrastingly, in the later western tradition, sport was thought of more as a distraction from the rigours of daily life, a pastime unconnected to any embodiment of culture. The modern Greek word for ‘culture’ – politismos – was only coined in the 19th century by none other than writer and patriot Adamantios Koraes. It bears no connection to the world of ancient Greece. If one had spoken of politismos in ancient Athens, one would have received puzzled looks. Politismos, if it conveyed anything to the ancient Athenians, would have meant the life of the politi, the citizen, and his (not her) engagement with the state. Culture was an entirely different phenomenon for the ancients.

Ironically, the discourse that surrounds modern professional sporting achievements is becoming more akin to the ancient ideal of sporting endeavour. While elite athletes across most sports are now fully professional and handsomely rewarded, there is a new sense that has developed in the last few decades of sporting achievement evoking a sense of glory and honour that the ancient Greeks might have understood better than we think. A lot of this is connected to the world of mass media, particularly social media, by which elite athletes partake in a more personalised engagement with their fans and are revered, or reviled, by them. They become demi-gods of sorts in the process, with the number they wore on their back preserved and ‘worshipped’ and their shoes placed in glass cases and gazed at by adoring fans. Even the products they endorse are lapped up by eager consumers keen to display their tenuous association with their idol.

But will Michael Jordan or Kobe Bryant ever be the modern equivalents of Odysseas and Achilles? Why are the latter, brutal warriors of questionable morality who would today probably be classed more as savage thugs than noble heroes, why are they thought of as commendable cultural representations of an ancient ideal, while the latter are often dismissed as popular, almost crass, icons. Is it because the formers’ deeds are heroically recounted in Homer’s engaging epic, while the latter are relegated to a lesser category of endeavour known since the 1950s by the demeaning term ‘popular culture’?

In 2008, while I was President of the Board of Trustees of the Powerhouse Museum, the Museum was offered Lady Diana’s wedding dress as part of a large display of her clothing and jewellery arranged in her memory by her brother Earl Spencer. We leapt at the Earl’s offer, not only because we truly believed that it would capture the public’s attention, but also because we saw it as an important collection of significant cultural value. Diana was not only a princess of the House of Windsor through her unhappy marriage to Charles, but she came to represent, rightly or wrongly, a public reaction to the staid and intransigent posture of the British royal family and its perceived lack of engagement with its subjects. As such, the exhibition was seen by our trustees as having intrinsic cultural value.

The reaction from Sydney’s cultural elite was deafening. According to some of our critics we had ‘degraded’ the decorative arts mission of the institution by selecting a frivolous exhibition of an attention-seeking princess’ clothes and finery. The Museum was apparently being ‘prostituted for popularism’. What was next? An exhibition of the clothes of Kylie Minogue, wrote one cultural doyen to the SMH? In fact, what that particular critic didn’t realise is that we already had Kylie’s famous gold hotpants in our collection!

More seriously, I attempted to correct the deeper point he missed in a letter to the editor of that newspaper the next day which I quote:

The Powerhouse has built its high regard by connecting with people of this city and not just with the cultured elite who sometimes like to keep museums and galleries to themselves. Would your reader have had the same objection to an exhibition about Marie Antoinette? I suspect not.

The Diana exhibition went on to become one of the biggest exhibitions ever staged at the Powerhouse Museum.

The passage of time makes the ephemeral or the popular – or even populist – seem worthy of study and reflection. Marie Antoinette was reviled in her time as a shallow self-seeking Austrian princess who had ‘invaded’ the French monarchy through her convenient marriage to Louis XVI. In the decades after her execution, as France lurched from republic to monarchy and back, she was thought of as unbecoming of worthy study. And yet, in museums around the world today her story, like Anne Boleyn’s, is now told and re-told. Stories become representative of a time in history – and humans have always loved a good story. It will be no different with Diana, I am sure. So what we learn from this is that what might seem trivial or light today sometimes takes on a new dimension over time. In a way, it becomes more ‘cultural’ in the process. It is no coincidence that the word ‘culture’ is etymologically connected to the word ‘cultivate’. Culture needs time to take root. The great sporting endeavours and achievements of today might now seem trivial to some, but they will persist, particularly if they become representative of a moment in time, just like so-called popular music of the 1960s, which defined an increasingly questioning generation and has thereby come to represent more than just the music itself.

So what we learn from this is that what might seem trivial or light today sometimes takes on a new dimension over time. In a way, it becomes more ‘cultural’ in the process. It is no coincidence that the word ‘culture’ is etymologically connected to the word ‘cultivate’. Culture needs time to take root. The great sporting endeavours and achievements of today might now seem trivial to some, but they will persist, particularly if they become representative of a moment in time, just like so-called popular music of the 1960s, which defined an increasingly questioning generation and has thereby come to represent more than just the music itself.

As any EPL fans in the audience would know, Manchester City begins every second half of its home matches with a rousing rendition of Hey Jude, and not because The Beatles were a Lancashire phenomenon. After all, they were from Liverpool, 30 miles up the road, Manchester’s Lancashire rival. But the song’s rousing chorus has the innate power to galvanise an audience into one voice before each second half begins and thereby create an intimidating atmosphere for visiting teams and supporters. I can attest to that, as I witnessed it a couple of months ago in a match at the Etihad versus Newcastle. The effect is simply overpowering, as much for the representative value of an era it evokes, as for the sheer wall of noise it generates.

But to become truly ‘cultural’ one needs more than mere sporting accomplishments. Returning inevitably to last year’s Grand Final, here is a previously-unpublished 3 minute time-lapse view of the entire day at ANZ Stadium, starting at daybreak and concluding when the last person left the field late in the evening.

What we all witnessed that day was undoubtedly more than just a team winning its first premiership after 43 years. This was, in itself, an amazing achievement, but it is not what historians will write about in 50 years. To achieve cultural significance the event needed more than that, in my view. And, of course, it delivered it in spades.

The underlying significance of the event for its fans was that this Club had openly defied big business, stood up for a principle it believed in, and had won when all the odds were against it. It had represented a community fighting back against a perceived wrong – and the community had won. This was indeed a cultural phenomenon and it only crystallised and became complete late on 5 October last year when John Sutton held aloft the NRL trophy that stands here beside me.

Alan Jones, with whom I regularly and openly disagreed during those difficult years in the courts and in the public protests, got it so right on the Town Hall steps back in November 1999 when he said that if South Sydney had been an edifice there would have been a heritage order slapped on it long ago and no-one – not even Rupert Murdoch – could have touched it.

Thankfully, the people to whom a sporting club mattered so much rose as one in those heady days and the edifice was saved from destruction. But it so easily could have gone the other way, and the scenes of jubilation you gradually see in this time-lapse photography before you now would have been the stuff of mere fantasy.

George Orwell once wrote that ‘serious sport has nothing to do with fair play. It is bound up with hatred’, he said, ‘jealousy, boastfulness, and disregard of all the rules’. Much as admire Orwell’s writing, I could not agree with him less. Modern sport is, in fact, quite the opposite, especially when compared to the more brutal corporate world or the intrigues of politics.

So, of course sport is a cultural phenomenon, even at its most basic level. Above all, it integrates members into a societal discourse and provides the cohesive glue that binds us together. It reinforces the learning of achievement orientations and aids in the imparting of social roles. And at its most fundamental level, sport helps complex modern societies cohere and, above all, as we saw in Manchester and in these amazing scenes from last October, builds people’s consciousness of togetherness like nothing else.

Sport as culture – of course!

Thank you.